Getting a hearing aid is a complex and expensive task, but the technology has come a long way

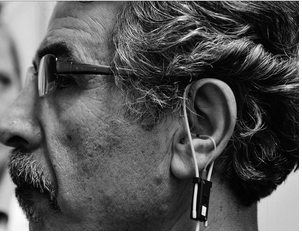

Abi Rezai is tested and fitted for a hearing aid by audiologist Sarah Helmel at Vancouver Hearing Centre on West Broadway. Getting a hearing aid can be a long, daunting process. Photograph by: Arlen Redekop, PNG, Files , Vancouver Sun Read Article:

Custom Protect Ear wanted to share this article with our audience because we promote hearing protection and hearing conservation news and technology. This article is about age-related hearing loss and how consumers can seek assistance when acquiring the new digital advanced hearing aids.

Decisions endless when it’s hard to hear

Abi Rezai is a stylish kind of guy who wouldn’t be shopping for hearing aids if they were still those bulky, putty-coloured jobs you can spot across a room. “I wouldn’t have them if it was like one of the big ones,” he said while being fitted for a second, tiny behind-the ear hearing aid that all but disappears under his hair. “Glasses,” he pointed out, “can be cool. But with hearing aids, it’s not the case.”

At 65, Rezai is part of a growing market that hearing aid companies want to cultivate – baby boomers who find it tricky to follow conversations, particularly in a noisy room, and don’t want to sit out the party. “I’d say, ‘Yes, yes,’ but I should be saying no,” he laughed. Rezai got one hearing aid four months ago and liked it enough to recently return to the Vancouver Hearing Centre to be fitted for his other ear. “It will never be like a natural ear when I was young, but it is better.” There’s no doubt that a lot of people could benefit from hearing aids. Studies in Canada, Europe and the U.S. have found between 20 and 30 per cent of people over the age of 60 have some hearing loss and that rises to 40 to 60 per cent in the over-75 age group.

Yet a report earlier this year in the Journal of the American Medical Association found only about 20 per cent of people with hearing loss ever get a hearing aid. There are plenty of reasons for that. For one, they’re expensive. A single hearing aid can easily cost from about $1,500 to $3,000 or more depending on the features. That’s almost always an out-of-pocket expense because they are not covered under medicare, except for children or people on social assistance. Some extended health plans through unions or the workplace offer limited coverage.

Nor do hearing aids cure a hearing loss; they amplify sound. So for most people who have gradual hearing loss over a number of years, walking out of the clinic into the blaring traffic can be overwhelming. Many give up.

Audiologists Sarah Helmel and Celia McDermott of the Vancouver Hearing Centre on Broadway said they usually adjust a patient’s hearing aid to a level that’s lower than normal hearing to let them gradually get used to all the noise they haven’t heard in a long time: the sounds of a house, the hum of the city, the scream of a siren. The devices can be adjusted upward when people are ready.

For University of British Columbia professor John Robinson, 59, the needs of his work left him no choice but to get a sophisticated hearing aid. He has been deaf in one ear since he was a child so when he found out the other side was starting to lose some sensitivity, he readily got one.

“It’s a big issue when I’m in meetings or giving a lecture or talk,” he said after a hearing test with McDermott. “Some people might feel it’s a sign of advanced age, but in my case, I felt I’d better have one good ear.”

Even with the hearing aid he still has some trouble making out questions from members of the audience in a large lecture theatre. That’s because hearing aids pick up ambient sound, making crowds the most difficult situation to navigate. Directional microphones inside the aids can pick up sound from a single direction, for instance, but can’t erase interference from someone coughing or whispering in front of that speaker. While digital hearing aids can automatically adjust to different environments – a quiet room versus riding the bus – the results are better than older models, but still not perfect.

Age-related hearing loss usually affects the high-pitched sounds first, in particular the sibilant sounds of consonants like “s” “f” and “th” and their counterparts in daily life. “It was a very weird sensation to crumple paper,” Robinson said of his first few days with a hearing aid. “These kinds of sounds were suddenly very audible.”

Newer hearing aids are digital and are programmed via a wireless connection to a computer using the information an audiologist gleans though testing hearing with recorded tones and the spoken word. The choices of features are complex and the key is to find the right aid for the right person. A younger, gadget-loving user might be keen to have one with a Bluetooth capability for phone calls, for instance. But an 85-year-old with arthritis in her fingers will want something simpler with larger batteries that are easier to handle.

Consumer Reports magazine produced some sobering research in 2009 that said shopping for hearing aids was tedious, expensive, and fraught with upselling and jargon. It used secret shoppers who later consulted with audiologists and found about 60 per cent of the hearing aids purchased weren’t right for the customer because they amplified too much or too little. It recommended that customers find a hearing aid dispenser who’s going to spend time with them, find out about their life and why they need a hearing aid, and discuss the pros and cons of various types and prices. In B.C., both audiologists and hearing instrument practitioners are allowed to test hearing and fit people with hearing aids. People sometimes start with a specialist like an ear, nose and throat doctor after being referred by their family doctor. That step is probably not necessary for age-related hearing loss, called presbycusis, because it doesn’t have a treatable medical cause, but is a general weakening of tiny hairlike nerve cells that sense and transmit sound in the inner ear.

Audiologists have at least a master’s degree in audiology – offered at several universities in Canada including UBC – following an undergraduate degree. Hearing instrument practitioners have two years of training at the college level. Both fall under the same governing body under the province’s Health Professions Act.

Brent Clayson is a Prince George audiologist who sits on the provincial council of the B.C. Association of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists. He said the complexity of options and need for adjustments requires ongoing interaction between a customer and a professional. Sure, you can buy some decent hearing aids at a good price online, but will they work the way you want right out of the box? “That’s why you want to deal with someone face-to-face,” said Clayson.

Read Full Article by Vancouver Sun.